So I am reading the autobiography of Mohandas K. Gandhi and in it he specifies that one of his lasting life regrets is that his penmanship was terrible. Given the difficulties and challenges of Gandhi’s life—his ongoing battles with colonial tyranny and his determined restraint not only from physical force but also from convenient falsehoods of any kind—I was startled to learn that this matter of having a ‘good hand,’ as it was once known, would have ranked so highly among his self-perceived failings. This was a man who struggled into his old age with sexual lusts, arranging to sleep alongside adolescent girls so as to prove to himself that he wouldn’t, and he didn’t, though the girls could have done without the experience. But mastering the art of scripted cursive was, by his own account, beyond him.

I wonder if it would have pleased Gandhi even in the least to know that today, some sixty years after his assassination, while the levels of human violence remain appallingly unchanged, the importance of handwriting has been fundamentally eradicated in the digital world. It is now relegated to brief Thank You notes inscribed (and sometimes calligraphically addressed) by the overzealous, and to adhesive notes slapped onto countertops that remind one to let out the dog or preheat the oven. I won’t even speak of electronic signatures scrawled with inkless stubs on plastic sheeting, soon to be replaced by data codes or genetic scans or anything but the mess of scratched letters. Yes, handwriting is still taught to children in their earliest years of schooling, but it is now taught as the drawing of pictures is taught—everyone learns to make a recognizable house or a capital A, but no one much worries over how far it goes beyond that, and it isn’t too long (fourth grade for my daughter, whose writing is sloppy, like I care) before teachers refuse to look at handwritten student work any longer.

Handwriting wasn’t always important even to Gandhi. As a young boy in India and as a law student in London, he was happily unaware of his inability to write neatly. It was not until 1893, while working as a young barrister for the repeal of anti-Indian racial laws in the British colony of South Africa, that he realized how repugnant his handwriting was and for how long he had been deceiving himself as to the extent of his progress in learning and character development. Gandhi recalled that when he “saw the beautiful handwriting of lawyers and young men born and educated in South Africa, I was ashamed of myself and repented of my neglect. I saw that bad handwriting should be regarded as a sign of an imperfect education. I tried later to improve mine, but it was too late. I could never repair the neglect of my youth. Let every young man and woman be warned by my example, and understand that good handwriting is a necessary part of education.”

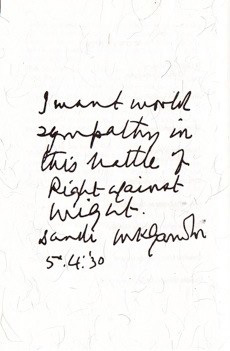

To be fair to Gandhi, who may seem here, in retrospect, to have been excessively harsh upon himself, his handwriting was in fact quite bad. I happen to own a copy of a 1995 anthology, published in India, of pithy and memorable Gandhi quotations. In it appears a facsimile of a moving note handwritten by Gandhi on April 5, 1930, the day on which Gandhi and his thousands of his followers completed the 240-mile Salt March from Ahmedabad to Dandi on the coast of the Arabian Sea, where, by making their own salt from sea water, they deliberately violated the British salt-tax edicts by an act of nonviolent satyagraha on behalf of Indian independence. Gandhi was shortly thereafter imprisoned by the British for the sixth time in his life, this time for nine months. The note, intended for distribution to the press, is brevity itself: “I want world sympathy in this battle of Right against Might. Dandi M K Gandhi 5:4:’30”.

But the orthography here provides a hurdle for even the most supportive of Gandhi’s intended readers. “Sympathy” appears to me, in Gandhi’s hand, as “agmpaltry” with the h, not the t, crossed, and “Might” easily scans as “Wight,” as does “Dandi” as “Sandi” and “battle” as “nettle” and “world” as “would” and “of” as “if” and “against” as “w/ainst” and “M K Gandhi” as “Wikipedia.” As Gandhi was sixty-one at this point, it is fair to conclude that indeed he had in the course of his adult life made no progress whatsoever in his penmanship despite his ample regret over the matter.

Surely this cannot have been a matter of sheer physical inability, even though I will readily grant that (1) Gandhi had just completed an exhausting trek for the causes of freedom and humanity, and that (2) my poking at Gandhi’s handwriting simply for the sake of showing how silly his views seem in retrospect now that all the world is a keyboard away and not even spelling much less handwriting matters will consign me to a deep deep hell reserved for essayists who mangle the lives of the great for the sake of their little narrative larks. But I may say in my own defense that Gandhi did manage to learn to spin cotton thread, a skill that demands, I should think, far more dexterity than accurately applying a finishing cross-stroke to the proper consonant. I hesitate to probe beneath the surface of a passage in an autobiography which Gandhi subtitled “The Story of My Experiments with Truth,” but I would have to say that his statement that he tried and failed in later life to improve his handwriting is an obvious evasion. Gandhi rued the happiness of his early years when language was a matter of vital meaning and even spiritual import regardless of how it happened to be written on a piece of paper. Intimidated by the practiced elegance of the correspondence and pleadings of his fellow South African barristers, Gandhi responded by chastening himself for his inner failings—an activity in accord with his ascetic spirit that more and more predominated as his life went on—rather than actually spending the hours per day for a week or two, max, that would have been all that were required to bring his handwriting up to speed. As I see it, Gandhi deeply did not wish to spend his time that way, not even for a week or two. If he had possessed any natural love for the now pointless art of shaping letters on paper, that would have revealed itself to him during even the most routine of his schoolboy practice lessons. (It certainly did for me. I enjoyed scripting my own initials and the full names of the girls I had crushes on. That latter was a form of innocent intimacy I think. Yes there was an aspect of possession in it, but possession of what? Certainly not the hearts of the girls. No, it was the possession of a tiny freedom—to express ardor, attraction, boiling life, to realize in my own tightly looped and hatcheted hand on my own spiral notebook pages, not the internet for all eyes like the kids do today, that writing was its own sort of caress.)

Now Gandhi, by contrast, was a man in pursuit of life’s spiritual meaning as expressed through committed political action. He didn’t want to fiddle with his penmanship—he wanted to get his ideas down on paper. Here is an event from Gandhi’s life that, to me, reveals far more of his relationship to handwriting than was expressed in his autobiographical warnings to future readers who will be reading his books on screens. Over the course of ten days during November 1909, while a passenger on the ship Kildonan Castle en route to South Africa after a series of frustrating negotiating sessions in London, Gandhi composed Hind Swaraj, or Indian Home Rule, generally regarded to be the most important of his political writings. It was handwritten upon the stationery of the Kildonan Castle, which must have been in copious supply, for the manuscript is 275 pages long. Gandhi was in a state of absorption such that he refused to leave off writing even when his right hand would begin to ache. His remedy: continue writing with his left hand to give the right a rest. Forty of the 275 pages, according to one scholar’s count, were written lefthandedly.

I do not know if Gandhi was ambidextrous, or if his task so possessed him that he made the hand unaccustomed to writing do the work regardless. I do know that a person who writes in this way must realize that stylish handwriting is as inessential to why we read as the shapes of notes are to why we listen to music. What matters are the words, the melodies. We will read and hear and see in many ways we never knew we could before it’s all done. These days Gandhi would have worked on a laptop computer. Later days than this maybe his thoughts could instantly appear as text in all the languages of the world the sympathy of which he wanted and was, I think, through struggle, given.