In the summer of 1970, it cost 50 cents to buy an issue of Caravel and 8 cents for Ben Hagglund to mail it to you. And maybe that was the ideal way to get one—by mail—his trip to the post office the last possible act completing a production cycle overseen start to finish by one man. It was Ben who opened the envelopes that escorted submissions to his desk; Ben, of course, who read all those poems and essays and selected which would make up the next issue; Ben again who hand-set the type for each issue, every letter and space of its 40 pages fingered by a human being; and Ben who printed the whole thing, by hand, on his own press. I like to imagine the postage stamp under his thumb, its scalloped edge smoothed into place with the rub of his skin. But by 1970 the mailing list was counted in the hundreds, so maybe this was where the machines finally took over, humming away and processing the collective bulk of so many little magazines at a cool 14 cents a pound.

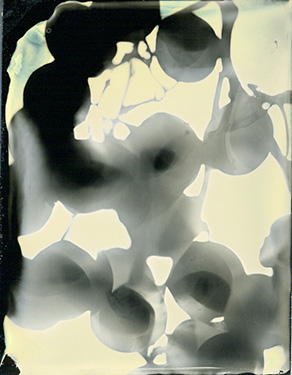

“Hand-set 10pt Century type and printed 4-up on a 10x15 Chandler & Price hand-fed platen press. Heads set in Cloister Black, Norway, Freehand, Century, Clearface, and others.” Even then it was an anachronism. The “entirely handmade publication” had already been supplanted by more efficient technologies, and Ben himself, champion of the simple life, wrote that “letting computers do routine tasks that formerly required tedious hand work” was part of creating a better world. Yet Caravel remained faithful to Gothic display types, leaf and lyre ornaments, and black ink plus a two-color cover (those two colors, in the Summer of 1970, being pea green and an orange dark enough to be red). This was certainly an aesthetic decision, and maybe something more.

We have printed in these pages about many lost causes and about vanished ways of life. The reason we did this, and will continue to do so, is that we feel that something of value can always be gleaned from the study of discards.

Certainly a disappearing technology suited the contents. While taking an “overall people-and-places theme” as its mandate, Caravel was in many ways preoccupied with loss, with the endangered and the exotic and if the magazine wasn’t exactly grieving, it was very sensitive to how things used to be, how they are in other parts of the world, and that all of it was vulnerable.

In the Summer 1970 issue, Issue #18, Val Richardson bemoaned the loss of places like “Heartbreak, Gutbust, Profanity Hill … leveled now by General Motors into bland varieties of Scenic Drive.” He, for one, was not going to be party to this forgetting, “So we call our road Snake Hill, ignoring street signs ignorant of wagon ruts under asphalt, or axe-men that blazed the way.” In Billy Dunn’s poem E.D. (which, at the time, signaled only the subject of the poem: Erasmus Dunn), a country preacher with an old Ford truck “died a martyr…Because advancing civilization and rising culture/Made it unsophisticated to speak in tongues/And wash the brethren’s feet.”

The urgency of this conflict, the friction between old ways and new, is suggested in the recurrence of war imagery paired with nostalgic scenes of rural life. Thomas Wright wrote in his poem “Safari” that, “when grandpa/ called, ‘A fox in the chickens!’ we went as/ if to catch Hitler…” Conversely, Julia Older’s poem “Czechoslovakia,” about Russian soldiers marching into Prague, ended in a dream of “the frenzied hen who wanders/From her eggs for a kernel of corn/And returns to find them gone.”

Transition, if not outright upheaval, was perhaps particularly on Ben’s mind that summer. Ben had established Caravel in 1957 from his home in Palo Alto, California, but when he retired in 1968, the magazine moved with him. Issue #18, then, was the first issue mailed from Thief River Falls, Minnesota. Ben chose Minnesota hoping to return to his hometown, but Holt was unraveling: a village steadily losing its commerce and its schools and its people. Holt, or what was left of it, might have been enough for Ben and Isabelle, his wife, but Caravel needed a town with a post office. So Ben took Isabelle and their cats and the press and settled 12 miles down the road, in Thief River Falls.

Ben had started writing editorial notes in Issue #15, summer 1966. Always informal, with Issue #18 they would become increasingly personal and eventually evolve into a forum to discuss everything from the Energy Crisis to Ben’s Cobalt treatments at the Veterans Administration hospital in Minneapolis—in adjacent paragraphs. Issue #18 brought the editorial notes from the middle pages to the very front, tripled their length, and changed the section heading from “Random Notes” to “Summing Up and a New Start.” Ben’s descriptions in that section of farms growing ever bigger and more industrialized, of young people siphoned off to urban places, and of small towns disappearing, are a familiar fact of Midwestern life anymore. Likewise, his characterization of modern life as a place where “computers do our stupid brain-fagging work” and “wars and more wars involving our country seem to make up our future” is all too familiar. Indeed, only the last page of the essay betrays the era in which it was written, its author pitted against “Vietnam warmakers, unflyable multi-billion-dollar airplane builders, and the like.”

Issue #18 also represented a shift in content. Tucked on page 24, sharing the bottom of the tenth and final page of poetry, a boxed note announced the new editorial policy to deemphasize poetry and shift attention to “the shorter forms of prose.” One essay per issue had been the previous norm, and here there were three, taking up almost half the issue, with Lawrence Estavan’s “Ezra Pound As Translator” perhaps the most telling of the new direction.

Some things, however, never changed. A three-masted ship sailing towards a lone night star washed across the front cover from issue to issue. Caravel continued to fill the back cover with a quotation. The contributors notes stayed in the front of the magazine, all nine or so of them there on page 2 like a handshake, the introductions before a conversation can begin. And there continued to be unpredictable gaps in the printing schedules, sometimes modest, sometimes a year or more. Ben gave up on it ever being a true quarterly, changed the masthead to “published irregularly,” and promised, “we will appear as often as we can.”

Issue #18 was a comeback and a harbinger and plain old business as usual. Ben himself couldn’t account for it.

When we made our decision to move, it crossed our mind more than once that it would be easier and cheaper and more sensible to call the whole magazine thing off, refund everybody’s money, and sell off all the printing equipment. But a magazine, especially after a dozen years and seventeen issues has a life of its own; so each time the dark mood would come on, something would happen to prove that the magazine wanted to live, in spite of what anybody else thought about it. And so the magazine keeps right on going on.