Until now, my appreciation for art history has been mostly a pleasant obligation of travel: I have visited the appropriate museums in the appropriate cities, uttering semi-appropriate comments along the way. (Then, on to the cuisine!) But not too long ago, I learned of something nearly impossible Vincent Van Gogh tried to do, and I still think of his courage.

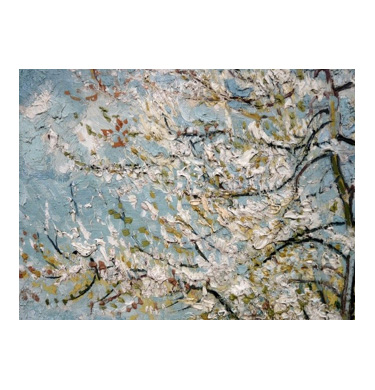

Eighteen months ago in Amsterdam, I viewed a triptych of Van Gogh’s orchards from the Provincial spring of 1888: The Pink Orchard, The Pink Peach Tree, and The White Orchard. I might not have lingered over those particular works had I not read the comment mounted next to them: Between 24 March and 21 April, [Van Gogh] made no fewer than 14 paintings of fruit trees in blossom. He hoped they would sell well: They were, he wrote, “motifs which everyone enjoys.”

Everyone? I asked myself. Joy?

It struck me as a tremendous risk. Here was an artist of great talent, attempting to traffic in happiness! Who does that anymore?, I wondered as I stared at the spring tableaux. And what ever happened to cheerful subjects in fine art?

It has long seemed to me that modern-day artists learn quite early that the goal is to astonish critics with creations that are darkly unexpected: raw, subversive, painful. Work that aches, stuns, saddens, inflames, gnaws, tugs—this is what artists who wish to be considered “serious” torture themselves to create. For it has been shown that in art, tragedy succeeds. God willing, it might even sell, if only after one’s suicide.

But then, here was Van Gogh: Skipping meals, dashing his letters, furtively staking out the orchards so he could have the bright morning sun all to himself and the easel. Sketch after sketch and stroke by stroke, in brighter and brighter color, it was a mad scramble to get all that joy onto the canvas.

It began in late February 1888, when Van Gogh fled Paris. He had come to loathe working in the city, all the downtrodden souls and drear and confinement. He left the apartment he shared with his brother Theo and traveled to Arles, in the countryside of Provence, in search of vivid color, fresh air, brightest light, and a heartier constitution. He was surprised to find his new home blanketed in snow—and almond blossoms already in bloom. The snow melted, and blossoms kept opening. After the almonds, there were plums, and later apricots and peaches.

Struck by their beauty and in need of his daily bread, Van Gogh began painting the orchards with the focused fear of a tightrope walker. Having for some time teetered on the brink of financial failure, the artist felt hopeful about improving his lot. That spring, a few of his paintings hung on exhibit in Paris; he had momentum, but lacked wider recognition. Now he wanted to make good paintings, to produce them in quantity, to break beyond the French scene and to interest new patrons in his work.

For Christ’s sake, get the colors to me without delay, the painter wrote to his brother, Theo, whose task it was to send art supplies from Paris. The season of orchards in blossom is so short, and you know these subjects are among the ones that cheer everyone up. His gamble went something like this: If I succeed in painting happiness, then I will be taken seriously.

One might call Van Gogh’s springtime of 1888 a misstep; all those endless bursting branches only a period of lower genius. But I won’t, because I agree with him about the mirth of spring blossoms. And so do the masses who buy Van Gogh’s Almond Blossoms second only to Starry Night images, trudging sore-footed and change-poor out of the museum gift shop with bright blue tubes tucked under their arms.

I agree with Van Gogh because one spring years ago, blossoms simply arrested me. Their frothy pinkness piped the curbs like cake frosting. Their bubble-gum fluff stuffed gutters, jammed my windshield wipers, fluttered in with the mail, iced trash cans like cupcakes. I was working for the newspaper in an American blue-collar town certainly no less dreary than Van Gogh’s Paris. There, I reported on cops who abused women, houses that burned to the ground, fights among millworkers and managers. Yet into my journal each night for a short time went blossoms, blossoms, blossoms, their candy pink petals a non-stop confetti as soft as fingertips, piling into ditches like endless parfaits, heaping at the bottom of the schoolyard slides, coming inside plastered to soles of my shoes. All through town for those few days, I could only gasp and shake my head.

I wanted the whole world to know. But the blossoms remained confined to my journal. For what could I do with them? To make art, I believed, I would have to undermine the blossoms somehow. Use them as a metaphor for despoiled innocence, the gloss on suburbia, or whatever unlovely aspect of seemliness I wished to satirize. But I liked those blossoms just the way they were, which seemed to make them an impossible subject. A decade later, Van Gogh’s orchards at last revealed what I had wanted to say, which was, simply, Blossoms!

Standing before his pink peach trees, I suspected it was too late for my blossoms. But perhaps there were other pleasant subjects for me. If I could find them—even just one—would I be daring enough to represent them as art? In my writing, I’ve blabbed secrets and revealed my insecurities and mounted some spectacularly flawed arguments. But to select a cheerful thing, depict it faithfully, and inscribe my name below? A move like that (to say nothing of fourteen in a row) could amount to the death of my career.

I know that I lack Van Gogh’s unselfconscious courage. Yet as the months have passed, I’ve found myself continually trying to answer: What subjects have cheered everyone up, right down through the ages, and will continue to do so into the future? As I tried to fill in the blanks, it seemed I could only rule things out. Babies, for example. I considered them immediately, vessel that I am of Western penchants. However, I decided to leave off my list anything that poops (even kittens) or speaks, because we have all pooped and we have all spoken, and we have all despised ourselves for those things.

I decided also to exclude the outcomes of human appetites, such as lust, hunger, and spiritual fervor. The thrill of orgasm, the taste of a ripe strawberry, and the euphoria of transcendence all satisfy cravings. But stepping out of your pension into spring’s soft yellow rays and crossing the weedy undergrowth of a fecund orchard, shading your eyes as old black branches proffer ruffled white cuplets to the bees… this is a pleasure with no corresponding appetite. It is higher than satisfaction.

A web search for “things that cheer everyone up” only added to my list of no-gos: a girl named Amber, a violet Swarovski crystal hedgehog called Spike, a trip to London, Shirley Temple, a laundry hamper topped with a plush badger, a newspaper misprint, the movie Pollyanna.

So I asked my friends what makes people happy. John wondered if I had heard of the laughter-therapy guy. Amy, who does bodywork, said her clients melt when she rocks them. “The moon?” wondered Wendi. I barely finished my question before Soudi declared, “a glass of rosé in the sun.” Almost everyone, in the end, mentioned something about the sun—blazing at the beach, shimmering in the park, pouring through open French windows while the coffee perks. Amy even raved about Philips Activiva light bulbs (the name of which she recalled off the top of her head), which simulate natural rays. The more I inquired, the fewer degrees I found between good cheer and sunshine. This made me wonder why the idea of a sun god had ever fallen out of favor. Here at last was a deity who made sense: a celestial body whose perfect proximity to Earth had given life and all the wondrous things humans have ever loved. Its gentle warmth allowed for fluttering petals, the glittering seaside in late afternoon, and a million upturned heads for a total eclipse. Also the balm of new-mown hay and the uplift of a peppermint stick. Plus the tinkle of bells in a bat-filled forest at dusk, the baroque of a calliope on a cobbled medieval square, and the dear chesty cello. To the sun, I tardily realized, we owe ourselves, and every diminished space between us: clasped hands, tousled hair, kissed lips.

And like any proper god, I thought, the sun is fickle. Witness the electrical disturbances caused by sunspots, cruel desert mirages, the poles in winter, melanomas, and outdoor wedding plans.

Still, it is a heartening thing, the sun, and I came very close to placing it on my list of happy subjects; maybe someday I would find the nerve to compose its portrait. However, I peered closer (I warned you I am no Van Gogh). Then I saw a blistered, bleeding thing, uneven and chaotic. Alas, I understood: Our sun fails the deity test because it is mortal. What is worse, it is middle-aged. Earth’s surface has already seen one of a final two billion years of life, which will end when the sun bloats itself to death, taking us with it. At which juncture, I suspect, no one will feel too critical of a brave artist who once tried to preserve happiness. Nor sorry about eight dollars spent on a pretty picture in a crush-proof tube.