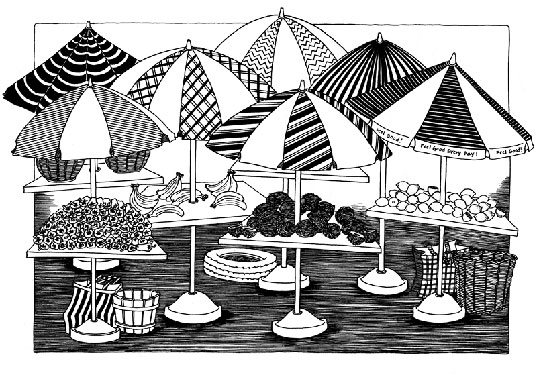

The Oshodi Market begins outside my open car window and spills over the railroad tracks. All around, pedestrians and motorcycles crush against lurching cars as the sun rises over the city. I’m supposed to be at the bus station in less than an hour. But here I am, trapped in a traffic thrombosis, an urgent pulse of metal and flesh that heaves forward, yet doesn’t move. I look out on a muddy street clogged with damp tables sagging beneath heaps of plantains and roasted peanuts.

Outside my window a boy clicks his tongue. I shake my head no. He clicks again, so I turn my gaze to the dense foliage of yellow canopies and wooden structures jammed against cinderblock walls, to green plastic tubs and frayed wicker baskets. From the underside of a concrete bridge, grey fumes mushroom up, then out; fingers of exhaust intertwine with the smoke of roasting corn. Garbage everywhere. Market umbrellas red and white read, Coca Cola, Enjoy. Underneath: dried, salted fish with opaque, shriveled eyes.

The car rolls just an inch. Stops again.

Two women fight over a cell phone—shout and push; arms ............

flailing, swimming in air.

The driver of my car, an educated man known as Papa Frank, must intuit my sensibilities—perhaps by my silence, or perhaps by the stiffness of my shoulders as I shift in my seat and poke my elbow at an awkward angle out the window. I have not voiced my appraisal of this place to Papa Frank, have not expressed my opinion of the density, the chaos, the dysfunction as I see it. This West African market feeds a slum, feeds a city: Cassava, yam, palm oil. Residents survive by selling what they can: used-clothes, DVDs. Illegal clusters of ‘Area Boys’ dispossess unsuspecting victims of their valuables.

With his knee pushed against the gearshift and one arm dangling out the open window, Papa Frank begins his dissertation. He speaks with the slow cadence of a university professor, telling me that the Oshodi Market is a microcosm of the city, of the whole country, too. “What you see here,” he motions with one finger in a circular motion, “what works, what doesn’t work, how this place functions in spite of itself—you’ll find everywhere in Lagos,” he waves his hand. The market is endangered, he says. It sprawls large, yet it’s compressed at the perimeter by an overpass ............

highway exchange, and smothered within by thieves. Police officials have long rallied to close the market down, while those same authorities also accept bribes to keep it open.

The shouting woman bumps her back against my door. Her bottom grazes my elbow, so I pull my arm inside.

My advice to the unaccustomed: Cover your watch; Look annoyed, not away.

Outside, drums thunder from beneath the bridge overpass—a vendor, I presume, demonstrating his wares: Batta ba-TON, the juju rhythm echos like a giant heartbeat, Batta ba-TON. The market pulsates—imperiled, alive.

Traffic moves and we pull away.

.

On the dirt street, the market finally behind us, yellow taxi vans are giant gnats—they dart side to side, weave through spaces that should be too small, then escape unscathed. Neighborhood ping- ............

pong players don’t notice the traffic just a few feet away. They grasp scrap-wood paddles and send the ball ticking back and forth across a warped table. For a makeshift net: a long, thin piece of wood balanced between two cans of condensed milk. Here in the slum, the defunct is refashioned, reused, trans-functional. Behind the boys, nailed at the corners of an open doorframe of a small shop, a dingy white sheet billows.

The juju drums of the market died out miles ago, but this part of the city surges with it’s own sounds, an arrhythmic cacophony of overlapping beats. Music blares from at least five or six boom boxes in the neighborhood: percussion, flute, cymbals, traditional vocal chants. Now add this: pspspspspspsssssssshhhhh—the tires’ spray of sogged earth, the angry honks of a thousand cars, the buzz of a thousand of motorcycles.

Traffic clots again.

A little boy in striped underpants and pink flip-flops sings nursery rhymes to no one in particular. He reminds me of the boy hawking peanuts at the market. Huha, the older boys shout, It hit the net, you’re out! The little boy sticks his tongue in the air and ............

smiles at me in the car.

Papa Frank says his country’s most recent military dictatorship ended just a few years before. “Democracy takes hold. Things are getting better,” he says to me, his captive audience. Nigeria’s success over the next few years will require two things, he insists: “Speed and patience.”

Gripped by land and by politics, the city squeezes 17 million people onto four islands within a broad lagoon. With only three bridges connecting it to the mainland, the burgeoning city’s traffic is intolerably compressed. The atmosphere: part frenzy, part apathy. The streets and markets swarm with activity—yet, according to Papa Frank, to actually accomplishing anything, like setting up an appointment or sending an email, falls somewhere between immensely difficult and completely impossible.

I think of the shouting women back at the market, and wonder who ended up with the cell phone. The woman who yelled faster and louder, or the one who stepped backwards and brushed against my elbow?

Papa Frank leans on the horn.

.

My view from an elevated bridge: The lagoon carves a thoroughfare for fishermen. A dead dog floats in the water with rubbish and human waste. Dilapidated swamp-houses lean on spindly stilts, hover just feet above the lagoon’s filthy surface. Women and children paddle dugout canoes through black liquid. Floods carry these fouled waters into the city streets where they stagnate, then shimmer with mosquito larvae: harbingers of malaria. Most residents lack sanitary sewage disposal. About half have no adequate supply of drinking water.

I recall an image from the market but say nothing: Salted fish with opaque eyes under red and white umbrellas—Enjoy.

I ask aloud, “How much farther to the bus station?”

Although Papa Frank ignores my question, he continues to speak with the tenor of authority: As OPEC’s fourth-largest oil producer, ............

he says, the country is oil-rich and human-rights poor. Foreign oil companies operate most of the petroleum wells, but they pay the Nigerian government more than half their profits. Petroleum accounts for forty-percent of the Gross National Product and eighty-percent of government earnings. But despite the country’s potential wealth, two-thirds of Lagos’s people live in abject poverty. Bribes to government officials and civil servants are regarded by everyone as unavoidable. Necessary. “Corruption is pervasive,” Papa Frank booms. “Rampant crime and violence. Tens of thousands of college graduates are un- or underemployed. The ‘informal’ or ‘black market’ defines the lifeblood of Lagos—illegal vendors on the streets. And out there,” he drops to a whisper, “‘Scam Capital of the World’ they call us.”

We inch past clinics, mosques, and apostolic Christian churches with musical names like the Eternal Sacred Order of Cherubin and Seraphim. Women carry outdated sewing machines balanced on their heads.

.

.

We pause at an intersection. Hordes of young men weave among vehicles, rapping their knuckles against hoods and fenders—a calling-card-knock querying interest. They offer every conceivable object: magazines, used shoes, mousetraps, envelopes of starch, bags of fruit juice, charger cords for mobile phones, sunglasses, toilet paper. Outside my window a boy, maybe fifteen years old, holds a fistful of tee-shirts while balancing a pyramid of toiletries and pharmaceuticals on his head. He stands between the median strip and our lane of cars. Leaning out, I buy a packet of Tylenol while the car idles.

“Five nira,” he says, and I hand him a twenty-nira bill. His name is Onochie, he says as he fishes his pocket for change. He’s from Enugu, about 200 miles northeast of Lagos.

“What a coincidence,” I say, “that’s where we’re headed, to Enugu.”

He smiles, excited that we have something in common.

“On our way to the bus station now.”

Traffic starts to move.

“God be with you,” Onochie says, now jogging along with us. “The road to Enugu is—how do I say? Not safe. Potholes. Roads washed out. A ten-hour journey, my friend—a slow go at best. Bandits with guns. Everywhere, you hear? In God’s name I pray for you, my sister. You would be safer to lay down in the middle of Oshodi Market covered in nira for the thieves. Ha, ha!”

.

On this April morning I catch the bus to Enugu. Before allowing anyone to board, the bus driver gathers all the passengers to pray. Such is customary before any road trip whether it be by taxi, hired van or bus. Fifty-some strangers huddle in a circle, palm-to-palm, heads bowed.

And I, too, the non-believer, I tilt my face in downwards reverence as well.

“Let the Almighty be with us today,” the driver shouts like an evangelical television preacher, his arms outstretched.

And from somewhere—a boom box? A car in the street? A neighboring shop? From somewhere, the juju beat thumps: Batta ba-TON.

Watch over us,” the driver wails. “Protect us from evil on this long journey.”

There’s a moment of suspension, a collective inhalation of silent breath—patience.

Batta ba-TON.

And the city sways in rhythm again: an exhale of car horns, motorcycle buzz, voices echoing the streets—speed.

.

Since I’ve returned from Lagos, government officials have targeted Oshodi Market, the boisterous street with shouting ladies and juju drums.

.

Oshodi Market Demolished

Famous for cheap prices, a haven for pick-pockets and notorious for blocking traffic, Oshodi Market has been flattened by Lagos State Ministry of the Environment. Officials of the MOE Task Force bulldozed all tables, stalls and sheds on Sunday morning. Authorities carried out the operation at 3:00 a.m., enlisting the help of Kick Against Indiscipline officials and the police. Trading materials were set ablaze. When traders came for early-morning business to discover their fate, some were allowed to salvage wares from their stores. Others, who arrived in the mid-afternoon, found their stalls burning. Thick black smoke still billowed in the sky at 3:30 p.m

(Daily Independent News, January 5, 2009)