Lawrence, MA, a former mill town forty years past its prime, was an unlikely candidate for Japanese influence. But the Dominican and Puerto Rican kids of Lawrence were just as susceptible as boys and girls in Japan, no matter that the town full of projects, triple-deckers and dilapidated brick buildings was a far cry from futuristic Tokyo, or that most parents probably couldn’t spare another ten dollars for a pack of Pokeman cards.

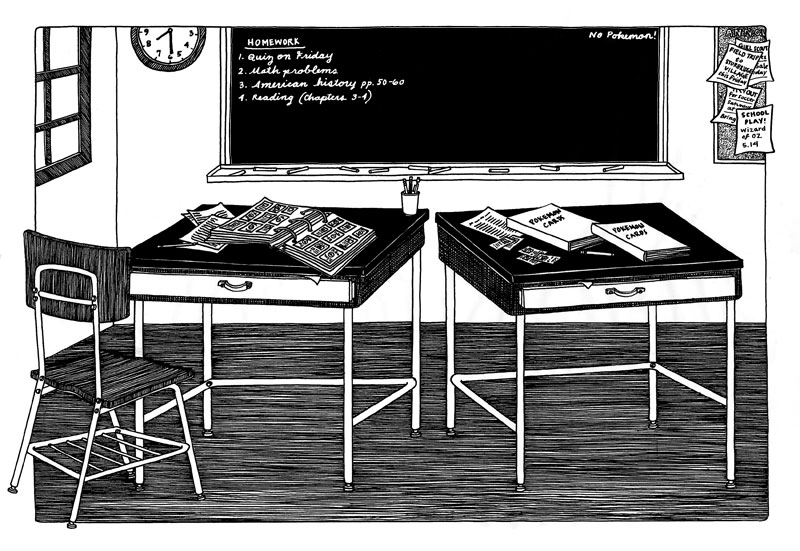

The teachers at St. Mary's grammar school hated Pokémon. Maybe it was the way the cards had children hustling like the drug dealers they were trying to prevent us from becoming. But what's addiction if it's not a nine year old spending his weekly ten dollar allowance on a pack of ten cards, only to rip them open in the car, realize none of them added a shiny holographic to his collection, pout, and then do the same thing all over again the next week?

“I got this one yesterday” said Reilin, the tallest kid in class, held back at least two years at school. He opened up his binder and show his Venasaur, the holofoil image of a half-plant, half-dinosaur shining through its plastic sleeve. Sebastian showed off his Blastoise, Christian even showed off his pink Clefairy because ............

it shimmered.

But we all knew who the king was: the holographic Charizard. An orange dragon, breathing fire, wings extended, with 120 HP and capable of 100 points of damage, the highest stats of any card at the time. That card glittered in the classroom lights, though it usually stayed tucked in the binder, an orange treasure that outshone the other rare cards surrounding it.

None of us actually played the card game. When you take things like rules into account, Charizard sucked despite its huge numbers (for example, it’s weak against water Pokémon). We didn’t care. It was badass, a fiery beast and not a cuddly Pikachu.

The only cards that could rival Charizard were Japanese holographics. Everyone in St. Mary’s Grammar School knew the flea market on Route 28 sold packs of Japanese cards. Sometimes the art was different, and that combined with the foreign text made them worth more. But then the new Pokémon came out in Japan, one hundred new monsters demanding our time and money. There was no official U.S. release for them, but you could buy Japanese packs of the new Pokémon at the flea market. They ............

were more expensive, but parents are surprisingly helpful enablers of addiction, willing to take you up the busy route and stand aside as you hand your money over to a gray-haired man or woman who, like your parents, called them “Pokey-mans.”

I only remember buying one pack of the new Pokémon, but that was all I needed to find the best card any kid in Lawrence had ever seen. It was holographic, with a picture of a huge, blue, Godzilla-like alligator. When the new Pokémon came stateside, it was named “Feraligatr.” At St. Mary’s, it was “better than Charizard.”

I brought it to school and Alex Montero wanted to trade for it. It wasn’t happening. Then he said the C-word.

“I’ll trade you my Charizard for it.”

I froze, then mumbled to myself, not sure what to do. I refused, but it was hard to stand my ground. The one card I always wanted, that we all wanted, for seemingly all our lives, was within my grasp. Every boy in class gathered around (most girls were struck by the inferior Spice Girls epidemic) to watch what ............

happened. Sebastian Mejía was at my side, speaking for me like Don King with a boxer after a rigged fight.

“No way, Alex,” he said to Montero. “This one’s better.”

“Come on,” Alex said, looking past Sebastian and at me.

“Don’t do it,” Sebastian said, still at my side.

Half the class said I should go for it—they were have-nots like me. Alex took the card out of his binder. He must have handed it to me, let me stare at the paper rectangle I had desired for a year, and see it sparkle in the dull yellow lights. It didn’t help that Charizard was my favorite in the videogames. Alex would’ve known that, too. Sneaky prick.

I said yes. With “no trade-backs.” It was the most controversial event in our class at the time, and would be until Mark – a student notable for being crazy and the only white boy in class besides my friend Chad – got kicked out of third grade for yelling “Fuck you” at our teacher.

Alex walked away, a small group following him, navigating through disorganized rows of desks to see his new Pokémon. Sebastian stood by me, shaking his head.

“You need to get it back,” he said.

I had never seen anyone back out of a no trade-back agreement – they at least paid for it, whether with more Pokémon cards, snacks at recess, or lunchtime milk cartons. I didn’t want to be the first, but I didn’t have a choice.

That afternoon at recess, instead of playing tag or bouncing a handball against the brick walls of the school, my classmates dragged me to Alex. A circle of kids surrounded us in the parking lot we called a playground, and not just kids from my grade. This shit was serious.

“We agreed no trade-backs,” said Alex.

A timid “yeah” was all I could manage. I didn’t want to go back on my word. But I had other kids speaking for me.

“It was a bad trade,” said Sebastian.

“Give him the card back!” yelled another kid.

“No trade-backs,” said someone on Alex’s side.

The back-and-forth went on until someone brought in a nun. She taught second grade and most of us knew her. She was a small woman but still stood above most of the younger students. Behind her tiny glasses you could almost see a flame in her hazel eyes, even at a distance. The circle broke, kids stood aside, holding their breath, and I think the “Imperial March” song played somewhere.

“You made some sort of trade?” she asked, staring me in the eyes first since I was closer, then Alex. We nodded.

“Do you want your card back?” the nun asked. I was on the spot. My brain stopped. I spoke without thinking.

“Yes.”

Alex gave my Japanese treasure back and I returned the object of my childhood desire. I said “goodbye” to it in my head, though I don’t think my classmates would have judged me if I said it out loud. I went home that afternoon to my family’s grey triple-decker and tucked the card away in my binder, a reminder that I had broken my word, still unsure of what I really wanted.

A year later I opened a pack of Pokémon cards. I fanned them out, and noticed an orange background on one of them. One hundred damage, 120 HP: Charizard.

My eyes widened. A smile started to curl. Then I took a closer look.

“No…”

It wasn’t holographic. It didn’t shine, didn’t shimmer, wouldn’t attract the envy of others, and didn’t complete my childhood.

I never bought Pokémon cards again.