I am five, and the Bristish empire is on its last wheeze. We live in Bury, Lancashire, in the north of England. Long miners’ strikes, which mean no coal for the fires that heat houses like mine are just around the corner. I see my mum navigating an old pram down to the railway lines to pick up coals that have fallen off trains. Mornings we use them to melt frost tracings on the windows. Mum pushes the cart. The road is steep, the pram laden with coal and I am skipping along beside her. She looks weary, and her fingers are dirty. The war is ten years over, but fresh fruit and meat are scarse. I have a gray ration book with my name on it. The unions are strong, the railways nationalized, and we children play in the scrap heaps of the war. We’re called Bevin’s babies—post-war kids brought up with the helping hand of the welfare state—masterminded by Ernest Bevin, Minister of Labor in the Socialist government that succeeds Churchill in 1945. We are weighed by a visiting nurse, who drives up to our house in a little Morris Minor and checks to see if we’re taking cod liver oil, rosehip syrup, and concentrated orange juice—fresh oranges still aren’t available.

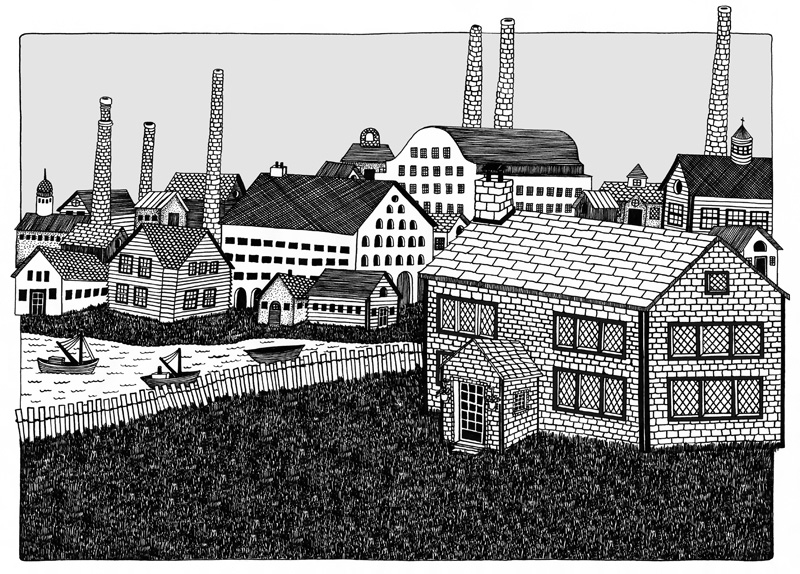

It’s the middle of the 20th Century, but the villages where I grew up, in Leicestershire and Lancashire, still look and feel Victorian ............

in many ways. Until I’m a teenager, I step into pea soup fogs each winter morning on my way to catch the steam train to school. Sometimes the fog—a dark gray blanket with an odd, lit from within gleam—is so thick my dad says, “You can’t see your hand behind your back.” I wait on the curb listening for cars, although sound is so muffled the few automobiles that pass leap out suddenly as if from behind a curtain. When I’m walking with a friend, I bounce along in the soft envelope, but on my own the dull sound of my echoing footsteps makes it seem I’m being followed.

The fogs will disappear along with industrial England and later will only hover above rivers in autumn like lonely ghosts. The blackened buildings will be cleaned, revealing golden sand stone underneath and transforming my understanding of 19th Century architecture. Uncle Freddie (actually, my grandmother’s uncle) will die just as the cleanup is under way, although he will maintain an attachment to the grimy past—to the way things have always looked.

We’re at a football match—Bury versus the Blackburn Rovers—and Uncle Freddie and I are standing behind the goal, and he ............

points to the skyline at the far end and says, “Count the chimneys.” I make out 50 tall, black towers that heat Bury’s mills and tanneries. “Soon there won’t be a one, but you saw them,” he says, appointing me their witness and the keeper of memories of this time. I come from the rubble and fog. I taste it, sooty and acrid, as I write. I hear the cold ring of my shoes on the flagstones, rushing to stay close to the stranger just ahead in the brown overcoat.